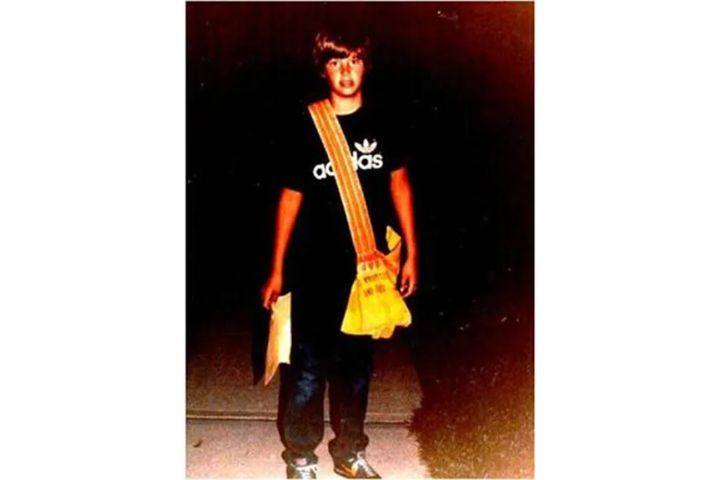

Early in the morning on Sunday, September 5, 1982, twelve-year-old Johnny Gosch set out to deliver the morning newspaper. This was a regular part of the boy’s routine. He would deliver the weekly papers in the afternoon, but the Sunday paper was due early in the morning. Unfortunately, this was no regular Sunday morning for Johnny. Sometime between six and seven that morning, Johnny Gosch disappeared. Johnny had gone missing from 42nd Street, and Marcourt Lane. To this day, Johnny Gosch is still considered a missing person, and it is believed that he had been abducted while on his paper route. It has been decades since Johnny went missing, but his cold case is considered open.

Normally, Johnny would wake his father up, and they would do the early morning route together. His parents were concerned about him doing the route at such an early hour, when the streets were dark and empty. It felt safer to have Johnny’s father go with him. The night before, Johnny had spoken to his father about how the other kids on their routes would do their routes alone — and they were all much younger than him. Johnny’s parents that him that he wasn’t given permission to do the paper route alone, and that he should wake his father in the morning as he always did. However, that morning, Johnny didn’t wake him up. Instead, he only took his miniature dachshund, Gretchen.

Johnny had started doing the route, because he wanted some pocket money. He was in junior high school, and having a paper route seemed like a good idea, as many local kids made money that way. Johnny liked to save up his spending money from the paper route, and go to the mall with his sister. He loved buying model rockets. He would often buy a single rose from the florist shop, to give to his mother.

Johnny David Gosch lived in West Des Moines, Iowa, with his family. He had two siblings, and his parents were John, and Noreen Gosch. Noreen was a secretary, and John worked at an agricultural supply company. Johnny Gosch was born on November 12, 1969, in Des Moines, Iowa. He had been a happy kid, quiet and friendly. Up until the day he was kidnapped, Johnny’s life had been perfectly ordinary.

The Gosch family lived in a fairly quiet neighbourhood, and it seemed like the threat of having strangers kidnap their children right off the residential street seemed like such a distant threat. There was a false sense of security that went with living in a middle-class neighbourhood, that their children would be safe. But children go missing in all sorts of neighbourhoods — rich or poor. And the Gosch family was about to have their whole life turned upside down.

John and Noreen Gosch only discovered that their son was missing, because their phone started ringing off the hook. Customers were complaining that they had not received their newspapers. At first, they were concerned that their son had simply overslept, so they went to his bedroom to check on him. But he wasn’t in bed, and they found that the dog, Gretchen, was missing as well. Johnny often took Gretchen with him, so that wasn’t unusual.

Johnny’s father started to travel along his son’s paper route to find out what had happened to him. Two blocks away from the family home, he found Johnny’s wagon, which was still full of undelivered newspapers. He knew then, that something was very wrong. His son was nowhere in sight. He quickly delivered the rest of the newspapers, then headed home.

As soon as he got home, John told his wife what he had discovered. The dog came home on her own shortly after. The Gosches immediately called the Des Moines police department, and told them that their young son was missing. They waited for forty-five minutes for the police to arrive and take their statement.

In the meantime, Noreen started calling the other paperboys who had picked up their papers in the same area as their son. Some of the other paperboys had seen Johnny that morning at the paper drop, picking up his copies of the ‘Des Moines Register’. One of the paper boys, named Mike, saw Johnny talking to a stocky man in a blue two-toned car parked near the paper drop.

Another witness, John Rossi, had also seen the man in the blue car. Rossi had thought that it was strange. Johnny Gosch told Rossi that the man in the car had been asking for directions, and asked if Rossi could help him. The man in the car drove away, but then it had returned shortly after. Johnny had told the other boys that there was something weird about the guy in the car, and he was going to do his papers quickly, then head home.

One of the boys had watched as a tall man walked towards Johnny to talk to him. The man had followed Johnny around the corner, and they were out of sight. Then, the boy heard a car door slam. A boy sleeping in his room nearby had heard this door slam as well, and had looked out the window to see a blue car speed away.

Rossi had glanced at the car’s license plate number at the time, but was later unable to recall what it was. He later went under hypnosis, and was able to remember a partial plate number. When the police checked the partial plate, they determined that it was a plate from Warren County, Iowa.

When the police finally arrived at the Gosch residence that morning, and began taking the Gosch’s statement, Noreen was able to tell them about all the information she’d collected from the witnesses. Paperboys who had seen her boy talking with unknown men, the description of the car — everything. Unfortunately, the police were not interested in what the parents had to say, and they were unconvinced that Johnny had been abducted. They informed Johnny’s parents that the missing boy couldn’t be classified as a missing person until seventy-two hours had passed. This delay was incredibly stressful for the Gosch family, and they were desperate for the police to begin the search immediately.

The police initially believed that Johnny had simply run away. They asked Johnny’s parents about the boy’s homelife, and if he had been unhappy for any reason. They were looking for something that would corroborate their theory that he was just another runaway kid. But he wasn’t.

A family friend worked with the parents to organize a local search, hoping to find Johnny. But there was no sign of Johnny, or his newspaper bag. Hundreds of volunteers had joined in the search, looking in parks, and vacant lots, wooded areas, and ditches. They searched the nearby state park located five miles away, and even the river. The search was difficult, because it had started to rain heavily after Johnny’s disappearance.

At one point during the search, Noreen Gosch had insisted that police chief Orval Cooney, had stood on a park table, and used his bullhorn to address the crowd of locals that were searching for Johnny. He told them that they needed to stop looking, because Johnny was just a runaway.

Given the fact that Noreen Gosch, and Orval Cooney had a poor relationship, Gosch’s version of events should normally be taken with a grain of salt — as it was likely her skewed poor opinion of the police chief. She had gone after him several times, calling him an ‘incompetent alcoholic’, while at other times referring to the police chief as ‘the town drunk’. She had attended city council meetings, bringing her attorney with her, and things had quickly gotten heated.

Orval Cooney seemed to have an equal amount of hatred towards Noreen. He said the following about Noreen Gosch: ‘I really don’t give a damn what Noreen Gosch has to say. I really don’t give a damn what she thinks. I’m interested in the boy, Johnny, and what we can do to find him. I’m kind of sick of her.’

But in this case, Noreen Gosch wasn’t the only one that thought poorly of Orval Cooney. He didn’t have a stellar reputation. At seventeen, Orval Cooney had been arrested in 1951. He had taken a teenage boy on a ride with some of his friends, and they’d severely beaten the teen. This had gotten him a thirty-day jail sentence, after Orval had pleaded guilty to assault with intent to inflict great bodily injury.

In 1982, the ‘Des Moines Tribune’ had published a story about Orval Cooney. They had interviewed eighteen employees from the West Des Moines police department — fourteen of which were patrol officers. When they were asked about their personal experiences they had working with Orval Cooney, the employees spoke out about how the police chief had physically assaulted a handcuffed prisoner, and that he frequently threatened and harassed his own officers.

They told the paper that there had been a burglary investigation that had been tainted, when one of Orval’s sons had been implicated in the crime. And there had also been repeated stories of the police smelling alcohol on Orval’s breath, and also seeing empty beer cans in the man’s vehicle. There were also racism allegations, in which Orval had allegedly used the n-word, and had also loudly spoken out about he’d refuse to ever hire women, or black employees at the police station.

When the article came out, the allegations made against police chief Orval Cooney was enough to begin an investigation into him. However, he faced zero repercussions for anything. Instead, the only ones who were punished, were the whistleblowers who had come forward. Many of the cops were reprimanded for coming forward, and two of the officers were fired outright. The reason given for them being fired, was misconduct that had taken place months before. There was some backlash from these officers being fired, and the paper published scathing letters regarding the issue. Oval Cooney was able to get through the investigation without getting punished for his abhorrent behaviour, and he also managed to keep his job.

The Gosch family struggled deeply with losing their son. Both parents were grieving, and it was hard to go on without him. But they knew that they had to keep fighting for Johnny, to try and find him, and get answers.

The police were still convinced that their son was a runaway, and they were doing little to try and find Johnny. There had been no ransom, and no motive that they could determine. When the Gosch family tried to work with the police regarding their son, the police were still insisting that Johnny Gosch had simply run away from home. They seemed stuck on this idea, no matter what Johnny’s parents said.

The Gosch family contacted the FBI, in hopes that they would investigate. But the FBI told them that they weren’t going to be very involved in the case at all. So, the Gosches started handing out photos of their son to the media. They had ten thousand posters printed off, which were sent to bus stations, gas stations, police, coroners, the media, anyone they thought might be able to help out. Johnny’s parents had also hired a sketch artist to draw the man witnesses had seen in the blue car.

The Gosch family believed that they were essentially doing everything possible in the investigation to bring home their son, believing that the police were still certain that he was a runaway. They were very vocal about their son’s disappearance, and got a lot of Des Moines residents to help them in their quest. Some people helped them sell chocolate bars, and other items in grocery store parking lots to raise money for private investigators, while others made shirts and hats with Johnny’s face on it. Local residents cared, and they wanted to bring Johnny home. It was disheartening, to think that the young boy was missing, and many parents feared for their own children’s safety. Parents kept a closer eye on their kids, and some even started making their children walk in front of them at all times while in public — as they feared that someone could run up and snatch their children away behind their backs.

John and Noreen Gosch kept in contact with people at different newspapers. They also spoke to people, and made appearances on TV shows to speak about their son. Not everyone had her back. Some saw her as a grieving mother, while others saw her as a crazy woman who was hysterical. Her public image was tarnished, because Noreen spoke openly about her disdain for the police, critical of how unhelpful they were.

Noreen Gosch kept going over everything in her memory, trying to figure out what had happened to her son. She felt like she must have missed something. One memory that came to mind, was an incident that took place two days before Johnny’s disappearance. The family had gone to Valley High School, to watch their son’s JV football game. Johnny went to the concession to buy popcorn. He didn’t come back straightaway, so his father went to check on him. He found his son under the bleachers, talking to a cop.

Johnny’s parents were curious about the conversation between Johnny and the police officer, and they asked him about it. Johnny didn’t seem upset by the interaction, and he said that the cop was being nice to him. But his parents were concerned. It seemed strange, that the cop would pull their son away from the crowd, and speak to him privately under the dark bleachers. When they asked Johnny why he’d willing gone with the cop, he’d simply explained that he’d talked to him, because people were supposed to do what the police said.

Johnny had pointed out the police officer to his parents, when they were preparing to leave the football game. Noreen made sure to get a good look at his face.

Later, once her son was kidnapped, Noreen recalled this incident. She wanted to try and talk to the police officer, to find out what had happened between him and Johnny. Before she could talk to him, she’d first need to figure out who he was. Noreen made an appointment with the West Des Moines police department. Then, she contacted the school board and asked for a list of all the cops who were hired to work security at her son’s football game. She brought this list to the police station, when she met with Orval Cooney.

During the meeting, there were photos of all the police officers laid out on the table, and Noreen Gosch was able to study them. Unfortunately, she couldn’t identify the man she’d seen at the football game in any of the photos. Noreen suggested that there might be some missing photos. Someone eventually got up, and returned with a few more photos. It was then that Noreen recognized the man who had talked to Johnny at the football game. They were able to do a process of elimination, and eventually whittle down the list of cops who’d worked security, until Noreen could determine who had spoken to her son.

Noreen wanted answers. When the school board had given her the list of police officers, she’d given a copy to the police chief, and kept a copy for herself. Noreen Gosch tried to ask if she could speak to the officer who’d been at the football game, to understand more about his conversation with Johnny. Unfortunately, police chief Orval Cooney was deeply angered by her suggestion. He threw a fit, shouting and stomping his feet. Orval insisted that Noreen was not allowed to talk to the officer. This led to Noreen thinking that he might be trying to hide something. The police officer was questioned later on, and it appeared that his conversation with Johnny Gosch had been unrelated to his abduction.

As the police began their investigation, they eventually changed their minds — and determined that Johnny Gosch had actually been kidnapped. It was estimated that Johnny Gosch had been abducted about twelve minutes after he’d left home that morning. Throughout the investigation, the police were unable to find any suspects in the case, and nobody was ever arrested for the boy’s disappearance.

In the month following Johnny’s disappearance, there had been a great deal of sightings around the United States. A young teen boy had been spotted on a street corner in Tulsa, Oklahoma. He’d shouted out for help to a woman standing nearby, and told her that his name was John David Gosch. However, two men had quickly grabbed him, and dragged him away. The woman had apparently not gone to the police right away, because she hadn’t been aware of the Johnny Gosch abduction until months later. She saw his picture on TV, and recognized him as the boy she’d seen in Tulsa.

Sightings of Gosch were reported in New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, and others. Somebody had seen someone resembling Johnny, with a man that looked like the person in the sketch drawing the artist had done earlier.

Each time a sighting was reported, the Gosch family were hopeful that it would be Johnny. But each time, they were disappointed to learn that it wasn’t. They wanted it to be him so badly, but their optimism was slowly chipped away, until they learned to lower their expectations — and presume each time that it wasn’t Johnny.

On November 12, 1982, the Gosch family celebrated Johnny’s thirteenth birthday, in a big celebration. It should’ve been a big event for the boy, had he been safe at home. But he wasn’t there to celebrate the big day. His family hoped desperately that they would get to reunite with him soon, but it had been months at that point, and he was still gone.

After Gosch had disappeared, there were two cases of young paperboys who had gone missing. Danny Eberle, and Christopher Paul Walden, from Omaha, Nebraska. Thirteen-year-old Danny had gone missing on September 18, 1983, in Bellevue, Nebraska. His brother had seen Danny talking to a man in a tan-coloured vehicle for days leading up to his disappearance. His bike and newspapers were found on his route, but Danny was gone. His body was found three days later on a gravel road, about four miles from his paper route. He had been bound, and stabbed multiple times, and stripped down to his underwear.

On December 2nd, 1983, twelve-year-old Christopher Walden went missing in Papillion, Nebraska. He’d disappeared about three miles from where Danny’s body had been found. Witnesses had seen a white man in a tan-coloured vehicle. He was found two days later near the train tracks. He’d been stripped to his underwear, and stabbed, though he hadn’t been bound.

Because of the fact that they were young boys around Johnny Gosch’s age, and they were paperboys who had been seen talking to strange men in vehicles. Could these two boys be somehow related to the Johnny Gosch disappearance?

In January 1984, the police discovered that the man who had killed both boys, was a radar technician from Offutt Air Force Base named John Joubert. He had a history of stabbing and torturing people since his youth, and was extremely sadistic. He had murdered a young boy in Maine, and had slashed multiple victims over the years. The FBI were able to finally track Joubert down, and arrest him. Joubert confessed to the murders, and was sentenced to death. He was sent to the electric chair on July 17, 1996.

Although at first people were quick to point out the similarities with the news stories of more paperboys who had gone missing, there didn’t seem to be a connection between the boys in Omaha, and Johnny Gosch. But Noreen Gosch and others were insistent that these cases were all connected. They were paperboys, of a similar appearance and age. And that was enough for Noreen Gosch.

Over the years, Johnny’s mother would continue to search for anything that might be connected to her son’s disappearance. She had at one point realized that a few months before Johnny went missing, the Gosch family had received pamphlets at their house from a religious organization called ‘The Way International’. Noreen insisted that because this religious cult had mailed pamphlets to her house, then they must’ve taken her son. She also stated that as soon as they had received the paperwork in the mail, her son had become withdrawn, and argumentative. He had, apparently, become deviant because of the cult’s mailed paperwork. The religious organization spoke out against her allegations, stating that what she was saying was ridiculous.

Noreen Gosch was fond of throwing around the ‘deviance’ angle around. During the ’80s, she would publicly call out homosexuals for being responsible for her missing son. Noreen Gosch was insistent that gay people were predatory towards children, and they needed to be investigated, simply for their sexuality. This included blaming NAMBLA (the North American Man/Boy Love Association), who believed in advocating for pederast/pedophilia relationships between men and younger boys. NAMBLA had been investigated by the FBI, and police over the years, though they had not been able to find evidence that the organization had kidnapped Johnny Gosch.

Throughout the years, a lot of people tended to look at the paperboys’ disappearances as the country’s moral failing, as people kept talking over and over about ‘the American Dream’, and the loss of innocence. They were young, handsome white boys from middle-class families, from regular suburban neighbourhoods. People kept describing Johnny as ‘all-American’, and talking about how children were expected to earn pocket money through paper routes. Having children going missing in such a way meant that parents were keeping a closer eye on their kids, and stating that their children’s innocence was getting ripped away. Parents started walking their kids to the school bus, or taking away their paper routes. Keeping closer tabs on their children, and teaching them that they needed to be fearful of strange men, in strange vehicles — lest they end up like poor Johnny Gosch. The missing paperboy became a cautionary tale, spoken about in hushed tones to younger children, parents fearful that their child might be next.

Neighbourhood Watch programs became extremely popular at this time, as parents were scared of letting their kids wander too far from home, and were determined to have everyone look out for children in the area. There were other programs cropping up, such as ‘Stranger Danger’, and ‘Operation Kids’, which tried to teach children about safety tips, and talks with local police officers. Locals in Des Moines were also encouraged to keep their porch lights on for the paperboys and girls, to keep them safer.

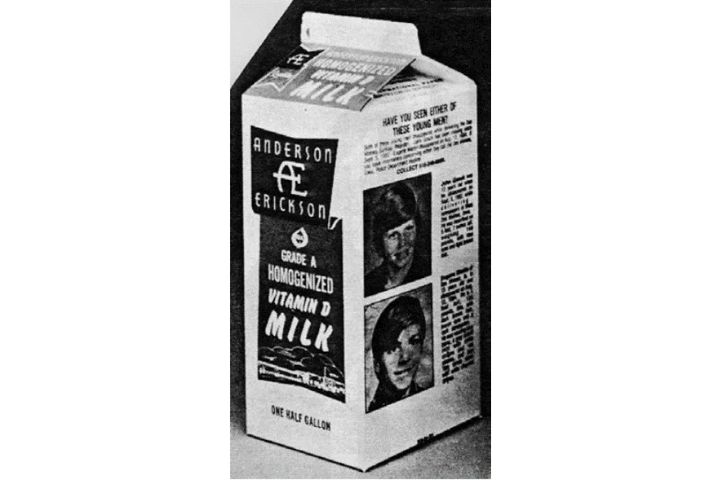

In September 1984, the Anderson-Erickson Dairy decided that they would put the pictures of Johnny Gosch, and Eugene Martin on their milk cartons. The dairy company was from Des Moines, and they hoped that this would bring more awareness to the two missing boys, as people would see their photos every day while they drank milk.

In December 1984, the nonprofit program National Child Safety Council, began the program called ‘Missing Children Milk Carton Program’, in hopes that someone might recognize the children, and help solve the disappearances. This led to milk cartons across the United States to feature missing children photos. Three months after it began, about half of the independent dairy companies had begun displaying photos of missing children — such as Etan Patz, Johnny Gosch, Eugene Martin, and others.

This practice of ‘milk carton kids’ continued on during the ’80s, though it was later replaced with the ‘Amber Alert’ system in 1996. The idea of putting the kids on milk cartons seemed to be good in theory — as so many people would see the children’s faces, and hopefully report to the authorities if they spotted the missing child. But it was also criticized for creating a lot of stress and anxiety in young children, as they stared at the photos during breakfast every morning. There was also the fact that white children were predominately chosen to be on the cartons, while black, or brown children were not represented as much.

Many of the milk carton children were never found. There were a few cases where the children featured on the milk cartons, were found dead. Children like sixteen-year-old Molly Bish, who had disappeared in 2000, while lifeguarding in Massachusetts. Her remains were found three years after she’d disappeared, located five miles from where she’d been abducted. Children like six-year-old Etan Patz, who had gone missing in New York while walking to his bus stop, and children like Johnny Gosch, and Eugene Martin, were never found.

The Gosch family had been determined to find out what happened to their son. They wanted him returned safe and sound, but the authorities had not been able to locate him. Noreen vowed to keep her son’s bedroom exactly the way it had been, since her son’s disappearance. She was determined to keep the porch light on, as a beacon for Johnny Gosch to come home. She held onto hope, believing that he was alive.

Noreen Gosch had been vocal over the years about her disappointment with the police department’s failure to bring her son home. She was critical about their investigation into not only her own missing son, but also the investigation into a great deal of other missing children throughout the years. Kids would go missing, and the authorities who should’ve been thoroughly investigating, just didn’t seem to care enough about the missing children to actually look for them.

In 1982, Noreen Gosch created the ‘Johnny Gosch Foundation’, where she would speak out at various seminars, and visit schools about sexual predators, in hopes of bringing awareness to the subject. Parents had become fearful that their child might be taken as well, and they started to keep a closer eye on their children.

Noreen Gosch lobbied for a new bill, titled the ‘Johnny Gosch Bill’, which would make sure that the police would immediately start searching for missing children, instead of waiting hours, or days that could be crucial. In 1984, the bill became law in the state of Iowa. Over the next few years, other states, including Missouri, introduced similar laws.

Retired Des Moines police chief William Moulder spoke out about the new bill, and about how instrumental Noreen Gosch was in creating change in the speed in which the authorities reacted to missing persons cases. He said the following: ‘The idea was that most kids come home on their own. But Noreen Gosch woke us up. That wasn’t good enough. If a kid is hanging out at a friend’s house for a couple of days because he’s pissed off at his parents, we should find that out. We should know. Noreen Gosch did what any mother should do, what any mother has to do in her situation: She kept hope alive.’

In August 1984, Noreen Gosch testified about organized crime, and ‘organized pedophilia’, during a series of Senate hearings. She stated that it was her belief, that rich pedophiles had organized kidnapping rings around the United States, who would kidnap young children to use as sex slaves. And it was her firm belief, that her son had been kidnapped by someone involved in this ring. She was also invited to the White House, for Ronald Reagan’s dedication ceremony.

Because of her testimony, Gosch started to get death threats. This would not deter Gosch’s quest for change, and justice in missing persons cases. The Gosch family had received a great deal of crank calls over the years, and had people contacting them with false stories, or scams about their son and his whereabouts. The police had been able to trace some of the phone calls — and found that they had been made by locals. Because the Gosches were so vocal about change, it made them targets for people who had poor intentions towards them.

Noreen Gosch went on to testify before the U.S Department of Justice — who would give ten million dollars to the newly-created NCMEC (National Center for Missing and Exploited Children). NCMEC worked alongside the Department of Justice, to help find missing children all over the US. They have thousands of cases today, which they are still trying to assist in locating.

John and Noreen Gosch hired a private investigator, to try and locate Johnny. The Gosches were desperate to get Johnny back, by any means necessary. And in Noreen’s case, this meant working three jobs to pay for the private investigators. Friends and neighbours had helped out the Gosches, holding fundraisers and selling candy. They had managed to raise about $200,000 in total, to aid with the high costs associated with finding answers. Noreen Gosch believed that they would be able to dig up enough information that she could hopefully get her son back. She refused to give up. The PI had done some digging, and determined that Johnny had walked a block north, to where his route began. One of the paperboys had witnessed a man following Johnny. The private investigator had talked to the neighbours, and one of them said that they’d heard a door slam. When they’d looked outside, the neighbour had seen a silver Ford Fairmont speed in the opposite direction of where Johnny’s wagon was later found.

Over the years, the Gosch family had hired multiple private investigators to find their son. One of them, had been Ted Gunderson (a retired chief of the Los Angeles FBI branch), and Jim Rothstein (a retired New York City police detective). One of the private investigators that had worked with Noreen Gosch, was a former Vietnam Vet named Sam Soda. In 1984, he had inserted himself into the investigation, as he approached Noreen Gosch, offering to help her with her son’s case.

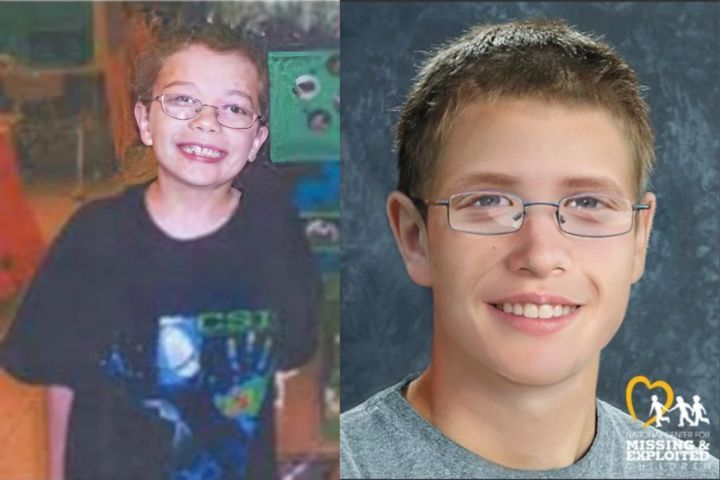

At one point, Sam Soda had called her into his office, and told Noreen that there would be another Des Moines boy kidnapped. He specified that this boy would be taken on the second weekend in August, in south side Des Moines. This turned out to be true. The boy taken from that location, was young Eugene Martin. He is still missing to this day.

In 1984, Sam Soda had passed himself off as a law enforcement officer. He exposed Frank Sykora, an employee of the Des Moines Register, as a pedophile. Sykora’s crimes were apparently not connected to the Johnny Gosch case, or any of the other missing youths from the area. But he wasn’t the only pedophile that had worked at the newspaper during the ‘80s.

Thirty-seven-year-old Frank Sykora was charged with child molestation, and third-degree sexual abuse. Sykora had been accused of fondling teen boys that would work on the paper route. He had told the young boys to sleep over at his house, as they would be delivering their papers early in the morning.

Sykora had allowed himself to be videotaped by private investigator Sam Soda, because the man had told him that he was with the police. But this was a lie. After he’d had the two-hour taped confession in his possession, Soda had turned it over to the police — and this was used as evidence to arrest the man. Sykora was fired from his circulation job at the Des Moines Register.

He was brought into the police station, and a polygraph test was conducted. There was no evidence to suggest that Sykora had done anything to Johnny Gosch, or any of the other missing teens from the area. Sykora gave a list of his victims to the police — which totaled fourteen boys in total. He pleaded guilty to the charges.

Over time, Noreen Gosch started to become suspicious of Sam Soda. He seemed to know a great deal about her son’s case. The police were also suspicious about Soda, and they started to keep tabs on him. As soon as they started monitoring Soda’s movements, the Gosch family became inundated with threats. Sam Soda was never arrested in the Johnny Gosch case, though he stayed on the police radar for years.

In June 1984, the Gosches got a phone call from a local man, who insisted that he had information about Johnny. Curiosity got the better of the Gosches, and they decided to meet with the man. However, they were unnerved to hear the man talk about their son’s case, because he knew a great deal about it. A suspicious amount. They considered it odd enough, that they told the police. Once they became aware of the situation, they started to keep tabs on the man. After their meeting, the family started to get prank calls. The prank calls went on for months. Most of the time, it was just heavy breathing, or hang-ups. People sometimes spoke on the other end.

During one of the phone calls, the man had told Noreen to drop her personal investigation into Johnny’s disappearance. Twenty minutes later, a strange man showed up in their backyard. He started to throw rocks at their windows. The Gosches called the police, but the man was never identified.

In August 1985, a Tulsa, Oklahoma man contacted Noreen and told her that he could provide her with pertinent information that would solve Johnny’s case. She was given information about what plane to take, and what Tulsa hotel to meet him at. She passed the information on to the authorities. When the FBI checked it out, they determined that the man had actually made reservations for Noreen.

The meeting sounded sketchy, so the FBI decided to send a female cop in Noreen’s place. When they held their meeting, the man was arrested, and did time for fraud charges. Noreen felt like her personal safety was at risk.

The police told her that it was a good idea to hold a press conference, and announce that they knew the identity of Johnny’s kidnapper. Shortly after this took place, the man that had been harassing the Gosches abruptly left town. They believed that the man’s sudden departure was an indication that he had been involved. The phone calls stopped, and for a while, things calmed down. He would later return to Des Moines, though he kept to himself.

In 1985, Noreen Gosch got a letter in the mail regarding her missing son. The letter had been written by nineteen-year-old Robert Herman Meier II, from Saginaw, Michigan (although it was signed ‘Samuel Forbes Dakota’). He wrote about how he had been a guard in the motorcycle club, at the same time that Johnny Gosch had gone missing in 1982. He told Noreen that Johnny had been kidnapped by the motorcycle club, as they were running a child-slavery ring. He stated that Johnny Gosch had been sold to a high-level drug dealer in Mexico City.

Meier asked the Gosches for $10,000, so that they could get their son back. He told them he’d leave further instructions in a phone booth miles away from the Gosch residence. The note told them to drive alone, and leave the money at the drop-off site, at one o’clock in the morning. Noreen believed Meier’s story, and was determined to do anything to bring her son back. Noreen contacted the police, letting them know what was going on. But unfortunately, she was unable to follow the instructions because she hadn’t had enough time. Meier called her, and said the following: ‘You waited too long, lady. You won’t get your kid back now.’

When Meier asked for $100,000 in exchange for returning their son unharmed, she was eager to comply. Meier was arrested in Buffalo, by the FBI at the US-Canada border. He was charged with wire fraud. When Noreen found out that Meier had been arrested, she was extremely angry with the FBI, and critical of their choice to press charges against him. She thought that Meier’s arrest would destroy any credibility from the Gosch couple, from anyone that would accept a ransom offer to get Johnny back.

In 1989, twenty-one-year-old Paul A. Bonacci confided in his lawyer, John DeCamp, that he had been kidnapped as a teenager and forced into sexual slavery. Bonacci had charges of molestation against him, and he was an inmate at a Nebraska prison.

He admitted to DeCamp that he had been forced to help kidnap Johnny Gosch in 1982. He said that he’d worked with three other men — who he identified as being named ‘Emilio’, ‘Charlie’, and ‘Tony’. He’d described the three men to his lawyer, and had positively identified ‘Tony’ as being the man in the composite sketch that the police had distributed. The man who he identified as one of Johnny Gosch’s kidnappers, was believed to have also kidnapped a young girl named Michaela Garecht in 1988.

Bonacci’s lawyer believed that his client was being truthful, as Bonacci provided details about the young boy that someone could only know if they had met Johnny in person. He said that Johnny Gosch had told him about sometimes attending his mother’s yoga classes, and how they would go to their favourite Mexican restaurant afterwards, called Chi-Chi’s. And Bonacci knew that Johnny had bought a dirt bike shortly before his abduction, which he had used to bike around on the empty lot beside his house.

The private investigator that the Gosch family had hired, Roy Stephens, began to look into Bonacci’s story. Noreen Gosch had given him a photo of Sam Soda, which they then used in a photo lineup. Once Bonacci had studied the photos, he’d recognized Sam Soda — and had even recalled the man’s name. Bonacci told the private investigator that Soda had been the local contact, for the people who had helped arrange for local Des Moines teens to be abducted.

There were hours of recorded interviews, of Bonacci talking about his past actions as a kidnapper. Noreen was given the chance to listen to the tapes. It had been nearly a decade since Johnny had gone missing, and she was desperate for any new leads in her son’s case. Noreen Gosch set up a meeting with Roy Stephens, so she could listen to the tapes.

She listened to Paul Bonacci talk in detail about his abusive childhood. At fifteen, he had befriended a boy named Mike in an Omaha park, who went on to introduce Bonacci to a man named Emilio. He created child porn. It was September 1982, and Paul Bonacci was invited to tag along with Mike, and Emilio, as they took a trip to Iowa.

The three of them stayed at a Des Moines hotel. At one point, another man had come in, with a paper bag crammed full of photographs. He had picked out the photo of Johnny Gosch, saying, ‘This is the one’. Bonacci said that Johnny had been chosen, because they believed that his eye colour, and hair colour made him more desirable — and they’d earn more money.

Bonacci realized that he was now involved in Johnny Gosch’s kidnapping, and he tried to get out of it. But the group were determined to keep Bonacci involved in their plot. Emilio took Bonacci out for a drive, so he could talk to him. He parked on the side of a dirt road, and pulled a gun on Bonacci. Emilio threatened him, saying that Bonacci had to help them kidnap the Gosch boy, or he would ‘blow Bonacci’s brains out right there and then’. That was all the convincing that Bonacci needed. Emilio drove the terrified teen back to the hotel room, where they began to work on their kidnapping plot.

They practiced repeatedly, to make sure that everyone knew their part. The group would be using three vehicles, and there were six people in total. Mike would be sitting in the back seat with Paul Bonacci, so that when the driver approached Johnny, the boy would see the two young teens in the car. The driver asked Johnny for directions, then he quickly drove around the block. Bonacci was instructed to get out of the vehicle, and talk to Johnny, in an effort to gain his trust. The group believed that this ploy would work, because Bonacci wasn’t very big, and would be less threatening than the adults. Bonacci was only fifteen, just a few years older than Johnny. His job also entailed luring Johnny close enough to the vehicle, so that they could abduct him without attracting too much unwanted attention.

Early the next morning, they put their plan into action. They drove to the area, and Bonacci got out and approached Johnny Gosch. One of the kidnappers, Tony, got out and grabbed Gosch. They both held a chloroform rag over Johnny’s mouth, knocking him out. Then, they put him in the car and drove away. Everything had gone smoothly, exactly as they’d practiced.

Bonacci continued to talk on tape about how they’d switched vehicles multiple times. The original car used in the kidnapping was driven out towards Chicago. The others drove with Johnny towards Omaha, then they later brought him to a house in Sioux City.

The kidnappers locked up Mike, Johnny, and Bonacci in a windowless room for the night, while they all went out drinking. In the morning, the three boys were forced to perform on camera, and the kidnappers said they were going to sell the video. Then, Bonacci was driven back to Omaha.

Bonacci went on to say that he saw Johnny Gosch a few months later. While on a trip to Colorado, he learned that Gosch had been sold to a man known as ‘The Colonel’. Bonacci discovered that the man’s ranch house had a raised floor, and there was a small area underneath where the kids would be held in captivity if they misbehaved.

When Noreen Gosch later met with Paul Bonacci, she was convinced that he was telling the truth. She went to the prison in Lincoln, Nebraska, with the private investigator. They were accompanied by a news crew from WHO (Des Moines). They filmed the meeting between Noreen and Bonacci, and some of the footage was used for the news. It was also featured in the documentary about Johnny Gosch.

Bonacci had not been informed about who was about to visit him that day, and so it came as a surprise to learn that Noreen was there to see him. He became distraught, and apologetic about the past, and deeply upset. Noreen had spent weeks working through her emotions before the meeting with Bonacci. She had a lot of anger and resentment for the man on the tape, who had confessed to helping kidnapping her son. She was trying to work on forgiveness, as she’d read in books about forgiveness being primarily for oneself, so that it wouldn’t eat away at someone like acid. When she met with Bonacci, she realized that he was not too far off from her own son. Noreen felt compassion towards the man.

Bonacci told her about Johnny’s birthmark on his chest, which had been widely reported when Johnny had gone missing. But Bonacci had gone on to tell her about the scar on Johnny’s tongue, and the burn on his leg — both of which had not been released to the public. He also told Noreen that he knew Johnny would start stammering when he was upset.

Although DeCamp, and Noreen Gosch both firmly believed that Bonacci was telling the truth about what had happened years before, the authorities didn’t believe his story. The police, and the FBI both decided against interviewing him about the kidnapping, and sex ring allegations, because they thought he wasn’t a credible witness. Bonacci’s siblings spoke to the police, and insisted that there was no way he could be involved — as he had been at home, when Johnny Gosch had been kidnapped.

In 1993, ‘America’s Most Wanted’ TV show asked Paul Bonacci to take them to house in Colorado, and show them where he had seen Johnny Gosch. Bonacci went with a camera crew, and showed them. The producer Paul Sparrow spoke out in the movie ‘Who Took Johnny’ about what he had personally seen. When inspecting the secret compartment under the floor, he had seen multiple children’s initials carved into the wood. Weeks later, the ‘Omaha World-Herald’ wrote an article about the house, and how the police had investigated. The article stated that ‘the sheriff’s investigators in Colorado had examined Bonacci’s claims about the house and don’t have any substantiation that Gosch was ever held there or that any laws were violated.’

Noreen Gosch claimed to have received a visit from her missing son in March 1997. She had gotten a knock on her apartment door, at two-thirty in the morning. According to her, Noreen had gone outside to see her son, Johnny. He was accompanied by an unknown man who didn’t introduce himself the entire time they were there.

Johnny was twenty-seven at that point, and he proved his identity to Noreen, by showing her a birthmark on his chest. He had been wearing jeans, and a winter coat over his shirt. His hair had been down to his shoulders, and dyed black. She recognized him as her son, and they hugged.

During the visit (which had been about an hour and a half), Johnny would continuously glance over at the unknown man for permission to speak. Johnny told her that he’d escaped from his kidnappers, and that he had been victimized by a Des Moines pedophile ring that took kids like him around the city. He had been cast aside once he was considered too old, and he told her he was terrified for his life. He told his mother that he was living under a fake name, because he didn’t feel safe enough to return home. Johnny refused to give her his address, so she couldn’t contact him after that visit. He had been warned that Noreen would be killed if he had tried to contact her, and he had feared visiting her in case someone retaliated. Johnny had told her that he wouldn’t ever feel safe, until the people who’d done this to him were arrested. He asked for Noreen’s help, in getting justice.

During their conversation, Johnny confirmed Paul Bonacci’s story, stating that after he’d been abducted, they had been locked up in a room together. Soon after, Johnny had been sold off to ‘The Colonel’, and transported around the country. He said that he was used by many rich businessmen, and politicians.

Noreen and John Gosch had divorced in 1993. John Gosch stated publicly that because he was not present when the visit between mother and son took place, he was uncertain if it had actually happened. There has been some speculation as to whether it had actually happened — and some think that maybe it was someone pretending to be Johnny Gosch. Noreen’s story about seeing her son years after his disappearance had led to a great deal of speculation, and conspiracy theories. The police were unable to determine if Noreen’s story was true or not, but Johnny Gosch is still considered a missing person.

Paul Bonacci, who had come forward in 1989 stating that he’d helped kidnap Gosch under duress, had stated in 2023 that he’d known about Johnny Gosch’s 1997 visit with his mother. He also stated that Johnny had visited him multiple times. He said that he knew that Johnny Gosch was still in hiding. He also said that he knew Johnny and his partner were expecting a child.

Noreen Gosch had written a book in 2000, titled ‘Why Johnny Can’t Come Home’. The book went in-depth into her son’s disappearance. She wrote about Johnny’s visit in 1997, and also wrote about the findings of the various private investigators the Gosches had hired.

In 2006, Noreen Gosch stated that she had found photos on her doorstep. There was a colour photo of three young teen boys bound and gagged, held in captivity. There was a black and white photo of a boy with a mouth gag, his hands and feet tied up. The boy had a human brand on his shoulder. Noreen firmly believed that the boy in the photo was her son. There was another photo of a man, who was possibly deceased. He had something tied around his neck. Noreen believed that the man was one of the people who had molested her son. She later posted some of the photos she received, on her website.

Two weeks after Noreen had received the anonymous photos, the Des Moines police department had received an anonymous letter. It said the following:

‘Gentlemen,

Someone has played a reprehensible joke on a grieving mother. The photo in question is not one of her son, but of three boys in Tampa, Florida about 1979–80, challenging each other to an escape contest. There was an investigation concerning that picture, made by the Hillsborough County (FL) Sheriff’s office. No charges were filed, and no wrongdoing was established. The lead detective on the case was named Zalva. This allegation should be easy enough to check out.’

Two of the photos were determined to be from a child pornography website. The children in the photos were later identified to be children from Florida.

When Nelson Zalva had been contacted (he had worked for the Hillsborough County, Florida Sheriff’s Office in the ‘70s), he was able to corroborate the details in the anonymous letter. Zalva said that the letter was correct, as he had investigated the photograph back in the seventies. He stated that he had also investigated the black and white photo (which Noreen believed depicted her missing son), in either ’78, or ’79, well before Johnny Gosch had disappeared.

Zalva stated that he had interviewed the three children in the photo. They had told him that nobody had been molesting them, or coercing them into doing anything sexual. He said that he could never prove that a crime had taken place, and so nothing had ever come of it.

When Zalva looked at the photos, he confirmed that they were the same photos he had seen decades before. He was asked to show proof that these were the same photos, however, Zalva was unable to do so. Years later, in the 2014 documentary titled ‘Who Took Johnny?’, law enforcement confirmed that the three boys in the photo had been identified. The photo of the other boy was still unidentified, and Noreen Gosch continued to state that that was her missing son. Both of Johnny Gosch’s parents were interviewed for the documentary.

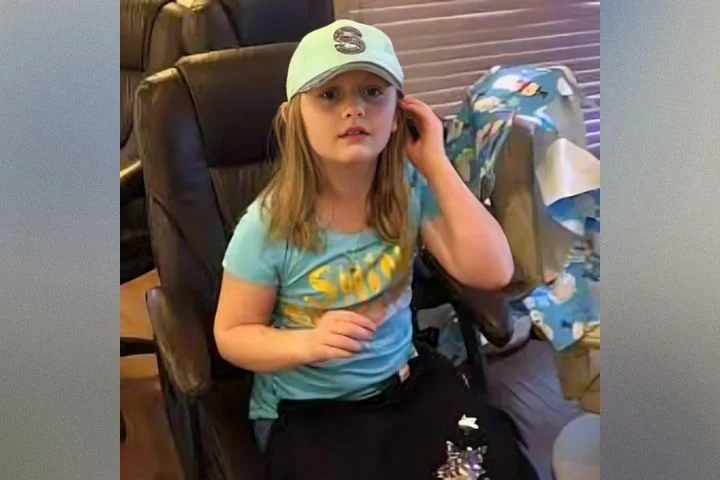

Noreen Gosch firmly believed that there were human traffickers all over the country — particularly in Des Moines. Over the past few decades, she had been aware of a great deal of other cases of kidnapped people — some of them were returned safely home. People like Jaycee Dugard, who had been held prisoner for eighteen years. Elizabeth Smart was kidnapped for nine months, before she was found. And there was the case of the three women (Gina DeJesus, Michele Knight, and Amanda Berry), who had all been held captive for years before finally managing to regain their freedom. Stories like this keep the hope alive for some family members, who want their loved ones returned safely. But sadly, many missing or abducted people are never found alive, and their families never get closure.